The room is quiet except for the rhythmic tapping of chef’s knives touching softly on maple cutting boards as they glide smoothly through firm carrots. The chef paces up and down the rows looking over the shoulders of his students, watching their efforts in creating the perfect julienne. “Remember,” he says, “if it looks the same, it cooks the same.”

The students repeat the mantra in their heads, as they learn not only the specific sizes of the cuts but the need to be precise as well. Cutting the carrots in a haphazard manner will overcook some and undercook others. Making the vegetables the same size will lead to more even cooking and an overall better product.

Knife skills are among the most rudimentary skills that a cook learns. They are also among the most important. Good knife skills can save time by making the work more efficient and save money by reducing waste and enabling you to use less expensive whole products rather than pricier prepared items. On the flip side, poor knife skills can be dangerous by putting fingers at risk.

GET SHARP

Among the most basic of knife skills is the ability to keep a knife sharp. As the saying goes, “a sharp knife is a safe knife.” Like any other skill, knife sharpening can be learned and must be practiced in order to perfect it. Knife sharpening starts on the stone, by creating a beveled edge. Stones come in a variety of grits—course, fine, and lots in between—and can be either water stones or oilstones. Hold your knife at a 22 1/2-degree angle to the stone. Using light pressure, run the entire cutting edge of the knife from tip to heel along the entire face of the stone. For every 10 strokes on one side of the knife, repeat with 10 strokes on the other. Start with a coarse stone and progressively work your way to a fine stone.

The steel is a device that will not sharpen a knife, but it will keep a sharp knife sharper for a longer time by honing or evening out the microscopic “feathers” on a knife’s cutting edge. Using the same 22 1/2-degree angle, stroke the entire cutting edge of the knife along the full length of the steel two or three times per side. If you do this every time you pick up your knife, you won’t need to visit the stone as often because the cutting edge will not round over and become dull.

PREPARE YOUR WORK AREA

With your knife sharp, you will immediately see your tasks becoming easier and more efficient. Another way to increase efficiency is to lay out your work logically. Place your whole raw product on a tray on one side of your cutting board, and keep another tray for finished cut items on the other side. Have smaller containers for waste and usable trim handy as well. Usable trim, such as carrot ends or onion stumps, make great additions to fortify a stock or sauce. Remember to keep some towels handy to wipe the cutting board in between foods, and always work with cooked or ready-to-eat products before raw ones.

MAKE THE CUT

Approach smaller or more delicate items like garlic or tomatoes with a paring knife. Its smaller straight blade gives you control and dexterity. Cut larger items with a chef’s knife. The longer blade makes for cleaner slicing, and its slightly curved, triangle-shaped blade and beefy handle offer leverage. To keep large, rounded vegetables like rutabagas or acorn squashes stable while cutting, make a small flat cut on one side so that they rest firmly on the cutting board.

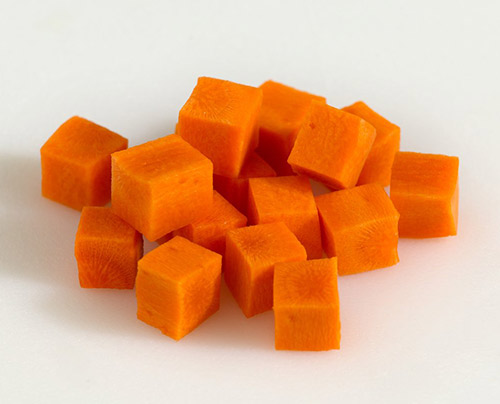

Many recipes call for “chopped” ingredients—what does this mean? Chopping refers to cutting vegetables into irregular but even-sized pieces. Use chopped vegetables for flavoring soups, stews, or sauces. Dicing, on the other hand, is more precise; ingredients are cut into cubes that are consistent in shape and size. Dice your vegetables when the vegetable will be a focal point of the dish. Mincing is a very fine chop that is often used for herbs as well as aromatics such as garlic and shallots.

KEEP IT CONSISTENT

Making perfect precision cuts, such as the long, rectangular julienne, is a laborious task that requires patience and good hand-eye coordination. The busy restaurant industry often does not allow the time or labor for precision cuts. As a result, chefs have developed a number of alternate methods to make comparable juliennes. Varieties of machines are available to cut vegetables into assorted lengths and widths, although they tend to be rougher on the ingredient and are less precise. Hand tools such as mandolins are good compromises between the precision you can achieve by hand cutting and the speed offered by a machine. A mandolin is a tool with a blade that will slice vegetables into varying widths, and teeth that crosscut the slices into juliennes in the same pass. All the chef needs to do is peel, trim, and cut the vegetable to length.

The other reality is vegetables do not really need such exacting specifications. They certainly do look good when they are perfect, but a small variation is acceptable. The goal when making precision cuts is consistency. It is fine if juliennes are not exactly 1/8-inch as long as they are uniform. Just remember the mantra, “If it looks the same, it cooks the same.”