“And I had but one pennie in the world, thou should’st have it to buy Gingerbread”

-Costard in Love’s Labour’s Lost, William Shakespeare c. 1598

When I was a child, one of my favorite holiday traditions was when my family and I would visit Mystic Seaport in Stonington, Connecticut for the lantern walk. The Seaport is a “living museum” that centers on the United States’ maritime past. There, the curators have recreated a 19th-century fishing village with typical houses and businesses from the period, as well as numerous fishing vessels and watercraft. Along the lantern walk, my favorite stop was in the tavern where we would drink hot mulled cider from pewter mugs and were served thick wedges of richly spiced gingerbread.

Jumping ahead several decades, I now teach the course Food History at the CIA, which is a project-based class as part of the Applied Food Studies curriculum. Over the semester, students research and curate a museum exhibit located on the Hyde Park campus that is open to the public. Through these exhibits, students to consider myriad ways in which food reflects social and cultural factors in history (class, race, gender, the role of technology), as well as how certain dishes themselves have changed over time. In the last couple of decades, museums around the world have either focused on food as part of a larger program, or in the cases of some, highlight a particular food (the curry museum in Berlin, German; the ramen museum in Tokyo, Japan, for examples).

There are at least four museums dedicated to gingerbread—in Alsace, France, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovenia. Clearly, gingerbread plays an important cultural role as food, as art, and as part of history.

But first, a problem….

Researching the history of gingerbread is more complex than one might expect. It is an issue of culinary history and definitions. According to The Oxford Companion to Food, gingerbread is “a product which is always spiced, and normally with ginger but which varies considerable in shape and texture.” (338) Broadly speaking, gingerbread varies from a hard cookie (sometimes made with ground nuts) to a moist and soft cake, and everything in between. And, as the definition above hinted, it does not even need to include ginger, which is the case of many of the dishes that translate to gingerbread in English, including French pain d’éspices, Dutch pepernoten, German Lebkuchen, and Slovene lect whose focus was historically more about a blend of spices, including pepper, and honey rather than molasses.

Because the ingredients and textures can vary so much, it also makes the origins of gingerbread even more debatable. Ginger is indigenous to Southeast Asia, as are cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Honey cakes were buried in tombs in Ancient Egypt and Greece with the 5th century BCE playwright Aristophanes penning in the Lysistrata “O why not finish and die? A bier is easy to buy. A honey-cake I’ll knead you with joy.” The 2nd century Roman cookbook Apicius, includes a sweet cake with pepper, pine nuts, honey, wine, passum (raisin wine), spelt, and hazelnuts. Several historians, however, argue that it was during the Crusades (1095-1204) when European Christians returned from the Holy Land with the spiced cakes. Due to the expensive spices used, it would be the domain of the wealthy, used as medicine, or to be eaten for special occasions. Cookbooks from the fifteenth-century England use saffron, powdered pepper, cinnamon, and honey decorated with whole cloves to make the “gyngerbrede,” while contemporary German manuscripts mention “gingerbread for sauce.” A century later, gingerbread still seems a far cry from what we know today. For example, the Sir Hugh Platt’s 1609 Delightes for Ladies, to adorne their Persons, Tables, Closets, and Distillatories, includes his recipe for “drie gingerbread” as follows:

Take a halfe a pound of Almonds & as much grated cake, and a pounde of fine Sugar, and the yolke of two new laid egges, the juice of a Lemmon, and a grains of muske, beate these together till they come to a paste, then print it with your moldes, and so drie it upon papers in an oven after your bread is drawne.

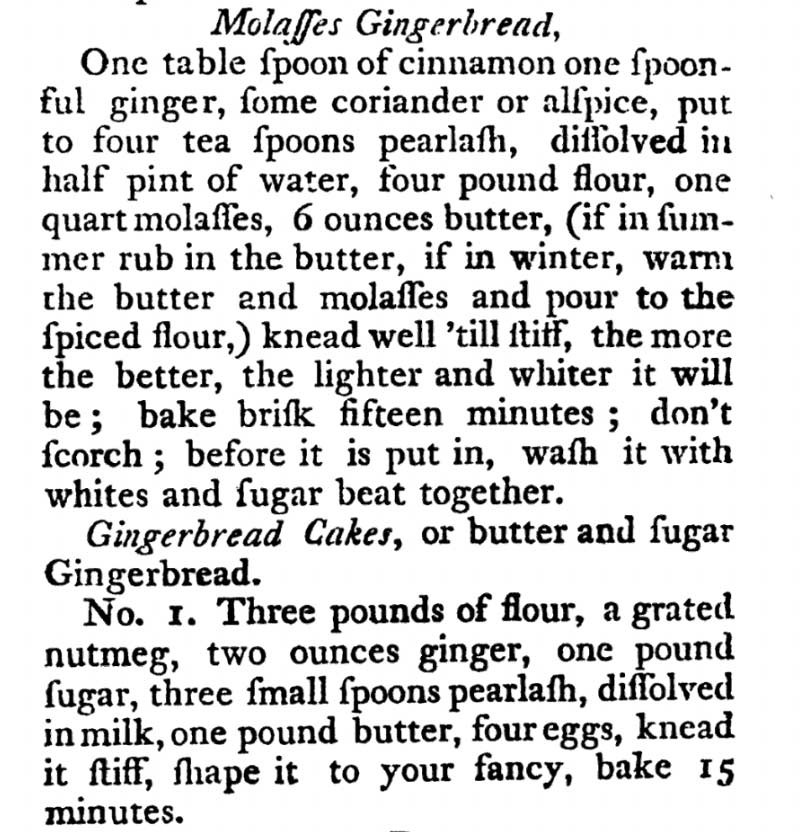

In the first cookbook written specifically for Americans and printed in the United States, American Cookery (1796), author Amelia Simmons included recipes for a variety of gingerbread including: “Molasses Gingerbread” “Gingerbread Cakes,” “Gingerbread baked in pans,” two more labeled “Gingerbread” and, sandwiched between them, “Butter drop do.” All of Simmons’ recipes use ginger (except the “butter drop do”) and many employ rose water with mace, coriander, and allspice appearing, but none include cinnamon or cloves. She also calls for pearlash (potassium carbonate) which reacts with acids (including molasses) to act as a leavener, which predates baking soda.

History on Display

To this day, the recipe used at Muzej Lectar (gingerbread museum in Radovljica, Slovenia) adheres to its historic roots of traditional honey cake; the spices used are cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, coriander, and anise (no ginger). Chestnut honey is the only sweetener, and hartshorn, a powder ground from the antlers of red stags, is used as the leavening agent. Once the dough is mixed, it sits for a minimum of two weeks, but it is best if left for six months, before being rolled out, cut, baked, painted, and iced.

The Muzej Lectar, located in a 500-year-old building, has been a site of making gingerbread since 1766. In 1822, the second generation of gingerbread makers transformed the space into a restaurant and inn, which remains to this day. The current owner, Jože Andrejaš, and his daughter, Mojca, also continue to make the gingerbread in the traditional shape: a heart, painted red (originally made from beetroot and blueberries) highly decorated, and often with a small mirror. Rather than a Christmas sweet, the heart-shaped treat was given as a token of love from a young man to his love interest. The female recipient would see herself in his heart and keep it. (If she did not reciprocate, she would eat the cookie!).

The Muzej Lectar, located in a 500-year-old building, has been a site of making gingerbread since 1766. In 1822, the second generation of gingerbread makers transformed the space into a restaurant and inn, which remains to this day. The current owner, Jože Andrejaš, and his daughter, Mojca, also continue to make the gingerbread in the traditional shape: a heart, painted red (originally made from beetroot and blueberries) highly decorated, and often with a small mirror. Rather than a Christmas sweet, the heart-shaped treat was given as a token of love from a young man to his love interest. The female recipient would see herself in his heart and keep it. (If she did not reciprocate, she would eat the cookie!).

The largest gingerbread museum is the Muzeum Toruńskiego Peirnika in Toruń, Poland, which traces its roots back to the 13th century and is housed in a 19th-century factory. It showcases material culture around gingerbread—historic cookbooks, traditional tools to make gingerbread, and even a Żuk truck that was used to deliver gingerbread, as well as conversations around labor and how technological progress impacted the making of gingerbread over the centuries. Tracing its history back to the medieval period, the museum includes archival material on gingerbread guilds who held the monopoly on gingerbread making in the Germanic lands and kings and queens who used gingerbread as both gifts and as political propaganda by distributing gingerbreads made in their likeness. The museum also has a permanent display on the relationship between gingerbread and fairytales, which highlights the cultural and artistic significance of gingerbread in history.

Gingerbread Houses

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, published first in 1812, is a collection of much older, medieval German morality tales that had been passed down orally. Included in this compendium was “Hansel & Gretel” which popularized gingerbread houses in Europe, but which had appeared in German by the 16th century. Today, across Europe and the United States, gingerbread houses continue to capture not only architecture and the artistry of their makers and has become part of Christmas traditions. Since the Nixon administration, the United States White House has displayed an “official” gingerbread house for visitors. (It is after all, one of the most famous American living museums and this year, the official White House ornament celebrates this tradition as it is a gingerbread house). Yet rather than being just a sugar-coated cookie, each piece of gingerbread tells stories of the past and of the present, of rich memories and sweet imagination.

Dr. Beth M. Forrest is a food historian and professor of liberal arts and food studies at the CIA and president of The Association for the Study of Food and Society. She is co-editor of Food in Memory and Imagination: Space, Place, and Taste (Bloomsbury, 2022) and a forthcoming book on sauce (Oxford UP, 2023). She completed an internship at Old Sturbridge Village Museum and is currently working on a chapbook on butter.