Sugar is the defining ingredient of candy making. It provides sweetness, bulk, flavor, mouthfeel, and preservation to candies of every description. Without sugar, there simply would not be such a thing as candy. In chocolates, the sugar is already contained in the chocolate itself, and we may add little or no additional sugar. In true candy making, such as hard candies or caramels, sugar is the principal ingredient and its sweetness is balanced by other flavors.

In most baked goods and pastries, sugar is added to other ingredients. But in candy making, sugar can be the only ingredient—or at least, one of very few ingredients. That’s because cooked sugar can be pulled, shaped, or whipped to create a variety of textures, from chewy soft caramel to a hard lollipop that cracks when you bite it.

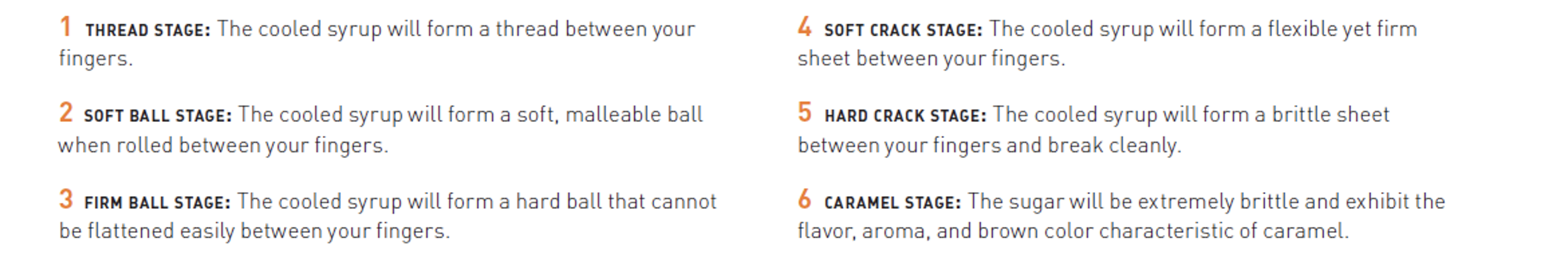

Sugar for candy making must first be dissolved in water and then cooked to a particular stage, depending on the finished product. Cooking the sugar serves to reduce the moisture level in the sugar solution, and the texture of the cooled sugar mixture will depend on the amount of water you evaporate—which directly correlates to the temperature of the cooking sugar. Lower temperature sugar solutions—240°F for “soft ball stage”—will contain more water, so the finished and cooled item will be softer, like a chewy candy. A higher temperature sugar solution—310°F for “hard crack stage”—will contain far less water, so the finished and cooled item will be hard, like the coating on a candied apple. The final stage of sugar cooking is caramelization, which can only occur when all the water has evaporated. This sugar will be brown and very hard and brittle. Caramel candies have added fat and other ingredients to make the candy soft and chewy.

This is the standard technique that should be used when cooking sugar for any of various uses. This technique can be used to cook sugar to any temperature and stage, from a syrup all the way up through caramelization. It is important to remember that the temperature to which sugar is cooked greatly affects how the finished product will turn out; accuracy is critical. Undercooking sugar typically results in a soft product that may not hold its shape well. Overcooking sugar usually makes the finished product too firm and difficult to work with and eat.

- Combine sugar, corn syrup (if using), and water in saucepan.

- Bring to boil over high heat while stirring gently with a wooden spoon or rubber spatula.

- Cover the saucepan with a lid and boil for 4 to 5 minutes over medium heat. This will allow the steam to dissolve and wash in the sugar crystals on the sides of the saucepan, helping to prevent crystallization.

- Remove the lid from the saucepan and return the heat to high. Place a thermometer in the cooking sugar.

- If there are sugar crystals remaining on the sides of the saucepan, wash them into the boiling syrup using a wet pastry brush.

- Cook to the desired temperature without stirring (your recipe will specify what temperature is ideal for the best results). However, when the batch contains an ingredient that can burn easily, such as a dairy product, nuts, or a thickening agent like starch or pectin, it must be stirred constantly during cooking.

- Use the cooked sugar as needed. The pan of sugar may be shocked in cold water to prevent carryover cooking.

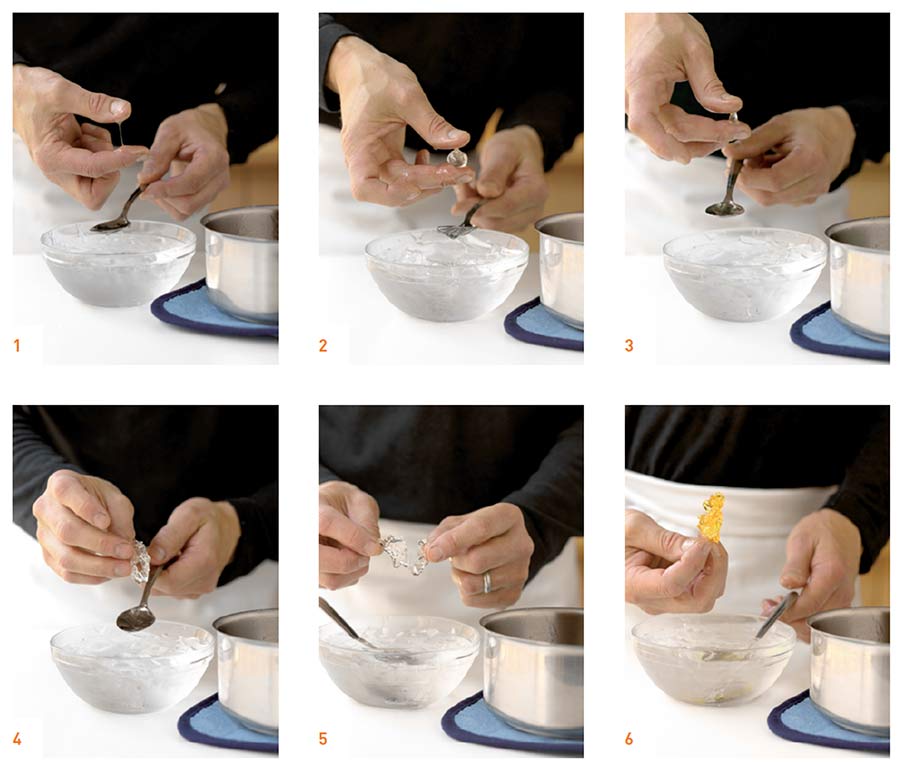

The most accurate way to measure the temperature of cooking sugar syrup is to use a thermometer; there is little reason that a home confectioner would want to use any other method. Finger testing is a time-honored technique that can be used in place of, or in addition to, a thermometer: dipping fingers in ice water, quickly retrieving a sample of hot syrup from the boiling pot with your cold, damp fingers, and immediately placing your fingers, with the hot syrup, in the ice water before you burn them. While professionals frequently use their bare fingers and ice water to check the temperature of cooking sugar, this technique is best not attempted by nonprofessionals. A similar technique can be used at home using a teaspoon.

- Place a small bowl of ice water next to the saucepan of cooking sugar.

- As the sugar boils, spoon small samples of the syrup out of the saucepan and immerse the spoon holding the syrup in the ice water.

- Allow the syrup to cool for several seconds, then remove the spoon from the water.

- Take the cooled sample of syrup between your thumb and forefinger and squeeze it to evaluate the consistency.

- The temperature of the cooking sugar corresponds with the stages of sugar cooking as illustrated below.

While this test is reasonably accurate in the hands of an experienced sugar cook, nothing beats the accuracy of a thermometer for achieving excellent results batch after batch.

You may recognize this technique in the Italian Meringue technique. The sugar, cooked to soft ball stage, whips with the egg whites and helps to create the structure which makes this variety of meringue so stable.